On the Taming of Luminous Interns, and Other Modern Follies

❦

2025-06-08

ai

technology

humor

commentary

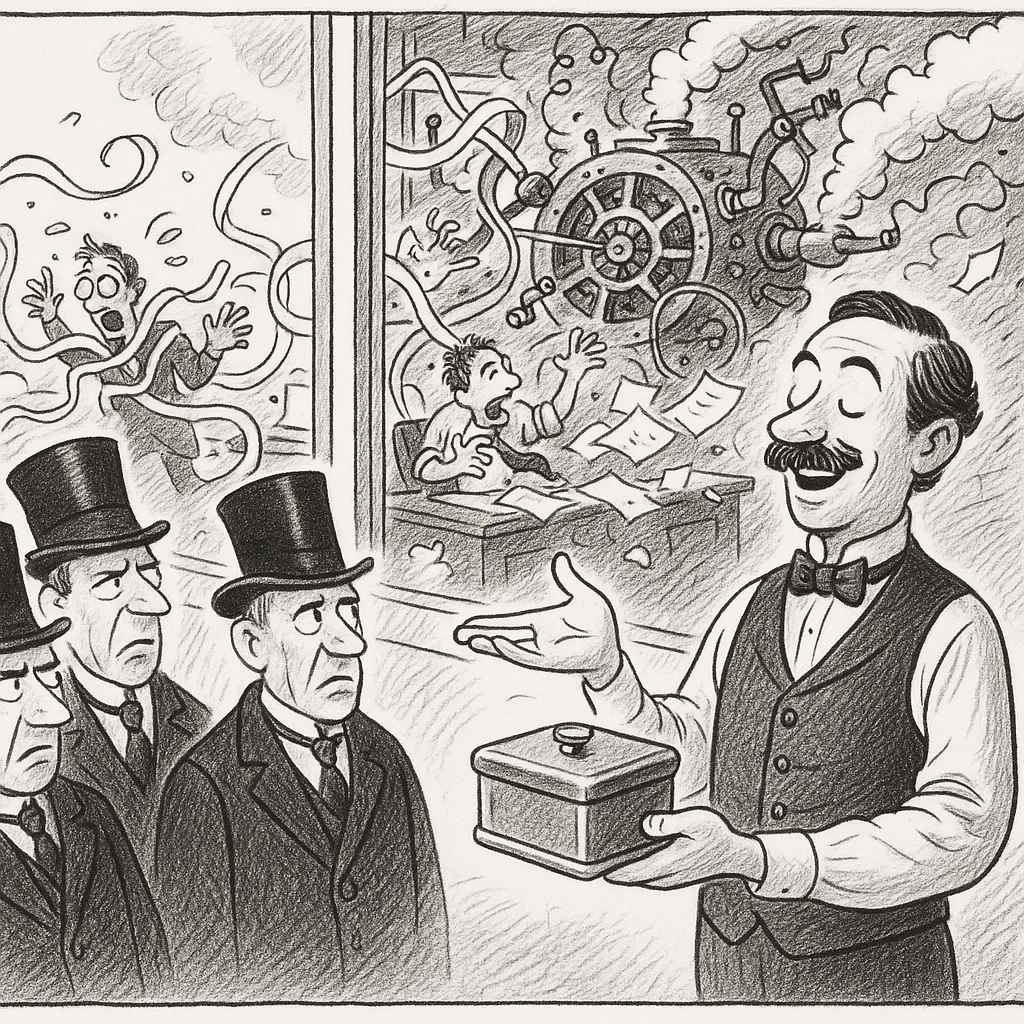

I have been a steamboat pilot, a printer, a prospector, and a purveyor of stories, and in my time I have seen a fair number of inventions that promised to do a man's work for him. Most of them ended up just inventing new kinds of work. This new contraption, this "Artificial Intelligence," is the most spectacular of the lot. It is like hiring a riverboat pilot who has memorized every map of the Mississippi ever drawn, yet has never once felt the pull of the current.

He is a wonder to behold. You can tell him, "Take me to New Orleans," and the engine will roar to life and the paddlewheel will churn with a fury you have never seen. But he is just as likely to get you there by way of the Ohio River, the Rocky Mountains, and a brief, disastrous detour through a cornfield, simply because a map he once read suggested it was a plausible route. He has a million facts but not a lick of sense. Left to his own devices, he will build you the most magnificent, intricate, and perfectly useless steamboat imaginable, and do it all before breakfast. This has taught me a few things about how to manage such a creature.

1. A Man Ought to Know His Own River

You cannot hope to pilot the whole world. A man is a fool who claims to know every river, and he will prove it soon enough. I learned the Mississippi, every bend and snag and sandbar, until I could feel it in my bones. So it is with this programming business. You must pick your own stretch of the river—be it this Next.js or that Ruby on Rails—and learn it so thoroughly that you know its lies. When your luminous intern suggests you navigate a reef by scraping the hull along the bottom, your own hard-won knowledge is the only thing that will give you the courage to tell him he's a fool, no matter how confidently he quotes his books.

2. Let the Youngsters Scout the Shoals

In my day, if you weren't sure of the channel, you sent out a small skiff to take soundings. You risked the skiff, not the whole steamboat. It is a lesson the world seems to have forgotten. When I am faced with a choice between two treacherous-looking channels—say, this "WebGL" and that "WebGPU"—I do not waste my time in the pilot house arguing about it. I tell my electric helper, "Son, you take this skiff and see how deep that channel runs. And you, take this other one and do the same." More often than not, one of them comes back with a busted oar and a story about a sandbar. That is information more valuable than gold. I have risked nothing but a bit of time and some imaginary wood, and I have saved my whole vessel from ruin.

3. Value a Good "No" More Than a Bad "Yes"

The most dangerous man on a boat is the one who will promise you anything. This electric brain of ours is such a man. He wants to please. If you ask him to build a fireplace in the powder magazine, he will draw you up the most elegant plans for it. You must teach him the value of an honest failure. I have a standing order for my own mechanical assistant, written down in a little book of rules. The first rule is this: "If you find you are building a fool's errand, you are to cease your hammering at once and inform me of the fact." An honest report of a dead end is the finest work a man—or a machine—can deliver.

4. Keep a Captain's Log of Your Follies

A man's memory is a faulty thing, prone to remembering his triumphs and conveniently forgetting the dozen times he nearly ran aground. The code my assistant writes tells me where we are now, but it tells me nothing of the whirlpools we barely escaped. And so, I insist we keep a log. A plain book, where we write down the day's journey—especially the foolish parts. "Tried to navigate the North Pass today. Found it to be a swamp. Made a note to never try it again." This log is the most valuable document on the whole vessel. It is a map not of the river, but of our own ignorance, and a good map of your own ignorance is the first step towards wisdom.

5. Build a Boat That's Easy to Scuttle

There is a great freedom in knowing you can walk away from a mistake. The architecture of my own little software enterprise is designed for just that. Every time we send out one of those little scouting skiffs, it is built in such a way that if it proves unseaworthy, I can pull a single plug and have it sink without a trace, leaving the main vessel entirely undisturbed. This knowledge gives a man courage. It allows him to try the wild, improbable ideas, knowing that the cost of failure is next to nothing. A man who is not afraid to be wrong is the only man who is likely to ever be right.